https://www.pinterest.com/miglesav/lithuanian-folklore-traditions-culture/

From my initial research stage and collecting images on a Pinterest board, what I was most drawn to was the patterns and shapes within the various paintings, textiles, wooden carvings, statues and etc. I especially liked how the textiles/clothing designs incorporate symbols for the natural elements, and how those can tell a story. Continuing my research, I began to look at Lithuanian folk art, and the ways in which old pagan traditions and folklore stories still have a role in modern day Lithuanian society and culture.

Lithuanian Folk Art

Source: https://ltfai.org/lithuanian-folk-art/

Lithuanian folk art is one of the oldest expressions of Lithuanian culture, as is proved by a variety of archeological artifacts. Over the course of time, the tree of Lithuanian culture branched out in three main directions: language, folklore and song, as well as folk art. The latter was influenced by the environment, the climate, various locations and resources, and also customs, which determined the purpose of the object, its form, its unique coloration and variation of pattern.

Until the beginning of the 19th century, Lithuania was mostly agricultural – 85% of the population lived on homesteads (farms) or small towns. For this reason, the homesteaders followed the traditions of their forefathers and fashioned their tools and themselves.

In his introduction to the book Lietuvių tautodailės institutas išeivijoje (The Lithuanian Folk Art Institute in the Diaspora, published in Lithuanian), Antanas Tamošaitis also speaks of buildings and tools that the Lithuanians fashioned by hand in distinctive styles. Chapels (in cemeteries and larger homesteads), wooden wayside crosses, farmhouses, furniture, spinning wheels, distaffs, towel racks, shelving units, spoons and other wooden cups and utensils as well as pottery. Other Lithuanian crafts are coloured Easter eggs, straw decorations (šiaudinukai), papercut art, wickerwork, and metalwork ornamentation, crosses and church spires. “Vilniaus verbos” are a unique ornate decoration made of dried flowers and grasses tied and woven together in patterns around a central stalk.

Every household had a hand-loom made by local carpenters, on which the females of the family were expected to weave all the necessary linens and clothing for their family, including their own wedding attire and distinctive sashes.

Every household had a hand-loom made by local carpenters, on which the females of the family were expected to weave all the necessary linens and clothing for their family, including their own wedding attire and distinctive sashes. Folk art was the expression of the homesteader’s soul and his most precious treasure, wrote Tamošaitis. He was very proud of the artistic level of our folk art, and his goal in life, as well as the mission of the Lithuanian Folk Art Institute, was and is to collect, study and preserve ancient folk art as well as to create and foster new folk art.

Lithuanian folk art is traditionally classified in the following categories, although not all of them are practiced in the diaspora.

Ceramics

Village potters had small workshops and provided the peasants with the necessary jugs, pots, plates, candleholders, vases, and figurines. Each potter developed his own characteristic style and made his own glazes. Ceramics were produced in two ways: 1) the pattern was applied to the greenware upon removal from the wheel, or 2) after firing, the pattern was painted on the pottery and then re-fired.

Costumes

The national costumes were known for the beauty of their colours, variety of patterns, and distinctive style. Until the twentieth century, a Lithuanian girl would weave her own wedding dress and costumes for festive occasions, as well as work clothes. The weaving technique, patterns, colours, and cut of national costumes are categorized according to seven regions of Lithuania: Aukštaitija, the Vilnius region, Dzūkija, Zanavykija, Mažoji Lietuva (Lithuania Minor), and Žemaitija (Samogitia).

Crosses

Lithuania is known as the Land of Crosses, and is famous for the Hill of Crosses near Šiauliai. The countryside is dotted with many ornamental wooden crosses and miniature chapel-posts or shrines erected at crossroads, in front of homesteads, and in cemeteries. They vary widely in style and ornamentation, and are an art form in themselves. There is a specific word for the folk artist who makes crosses: “kryždirbys”. The carving of crosses (cross-crafting) was recognized as a UNESCO Immaterial World Heritage art as of 2001.

The famous Hill of Crosses, a pilgrimage site for several hundred years, is a testament to Lithuanian faith and perseverance. During Soviet rule, the crosses were destroyed with bulldozers more than once, and locals would rebuild them almost overnight. There are over 200,000 crosses on the Hill.

Easter Eggs

The colouring of Easter eggs with natural dyes was a very popular tradition among the peasants. Either a pattern was applied to the egg with wax before dyeing, or else the whole egg was dyed first and patterns were made by scratching away the dye in certain areas with pointed tool. The ornamented eggs were used as decorations for the festive Easter table and as gifts. The patterns used for eggs decorated with wax are distinct from the motifs and composition used for the scratch technique.

Jewellery

Amber has been used for adornment since Neolithic times. Lithuanians have always loved this semi-precious stone, Baltic Gold, and endow it with healing and magical power to this day.

Metalwork

Iron crosses and church spires another iconic art form, and are often used to decorate cemeteries, monuments and memorials. Many of their motifs hark back to pagan times. Blacksmiths also forged tools and other farm and household items.

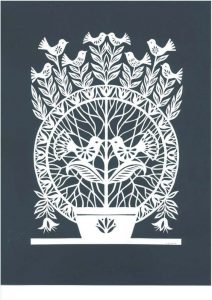

Papercut Art

In Lithuania, paper cutting has been practiced as an art since the 16th century (some sources say – the 14th) and was especially popular for decorations at weddings and other special events. By the end of the 19th century, it was widely used as decoration for the home – to cover a window, trim a shelf, a lamp or a mirror frame.

Straw Art

The art of straw ornamentation is a folk art brought from Lithuania by post WW II emigres. As in the area of weaving art, Antanas and Anastazija Tamošaitis were instrumental in promoting and preserving this craft, and Antanas had prepared the material for a book on this subject in 1988-1989, “Lithuanian Straw Art”. It was never published, however, the Lithuanian Folk Art Institute is pleased to present excerpts from the manuscript here, exclusively on this website.

Textiles

Until the 20th century there were no textile mills in Lithuania. Peasants would spin linen and wool, and weave all their own cloth to make their garments, bedspreads, bed sheets, towels, and tablecloths. Sashes were woven not only for use as belts, but also as gifts and special mementos. Each family had its own loom. The custom was that a bride would take to her new home at least two dowry chests of woven cloth for the future needs of her family. These were her riches, and a matter of great pride. Lacework, knitting and crochet are still very popular, and the traditional patterns often echo the motifs used in weaving.

Wood Carvings and Woodcuts

Simply but profusely carved towel racks, distaffs, spoon holders, and spoons, along with the spinning wheel, loom, and decoratively painted dowry chests, contributed to the cozy home atmosphere.

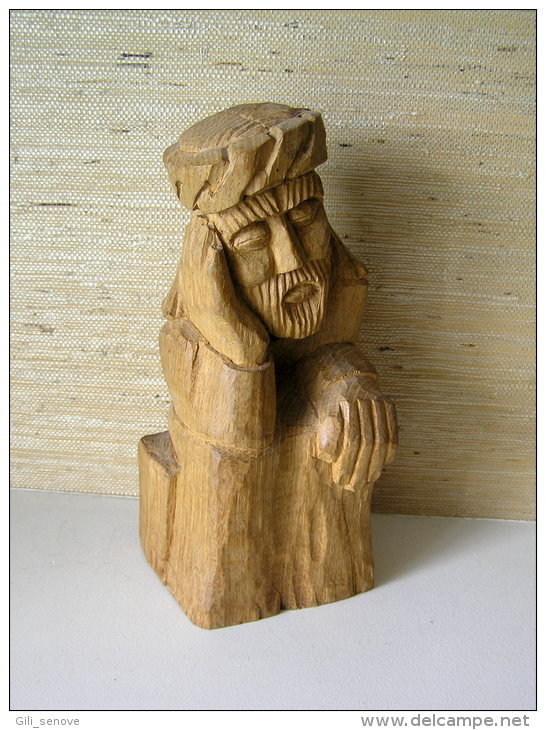

The seated figure of a pensive Christ became the symbol of Lithuanian folk art sculpture. Carvers also made various musical instruments out of wood, especially “kanklės”, a type of zither.

Paintings were mostly of saints, painted in oils on wood by amateur craftsmen. Woodcutters also engraved pictures on wooden blocks (woodcuts), coloured them, and made prints.

Lithuanian Sashes

Source: http://thelithuanians.com/bookthelithuanians/node35.html

Sashes are produced by twisting, twining and weaving techniques. Sashes, found in ancient burial places, date back to the 4th and 5th A centuries B.C. Now, twined and woven sashes are the most popular. Earlier, several score of motifs were used in sashes. Symbols of the celestial bodies predominated, such as crosses, stars, and very often a six-pointed star in a rhombus. Frequent were the motifs of fir-tree, blossom, bud, rake, and tree of life. Because of the weaving techniques plant motifs are similar to geometrical patterns and sometimes it is very difficult to differentiate between them.

In the world outlook of the ancient Lithuanians the circle symbolized the sun. It was also used as a protection against evil spirits. The circle is a symbol of the sun, virtue and warmth. A sash with sun symbols, girdling a person's waist, makes a circle around him. In this way, a sash practically symbolized two things.

The patterns of twisted and twined sashes are less complicated, they usually consist of stripes, squares, herring-bone, teeth, rhombuses. Twined sashes are made of wool yarn and no tools are used for that.

Every girl was supposed to know how to make sashes. After their wedding, on their way to their new homes, brides used to tie sashes on wayside crosses and trees and then on the gate of their husband's homestead to ensure their happy conjugal life. Brides used to leave sashes at every place they were likely to frequent in the future - at the fireplace, the wellsweep, the bathhouse. Sashes were used as presents for the musicians at the wedding and neighbours. Sashes were used as part of the swaddling for babies, particularly when they were taken to church to be baptised, also to support bast baskets while sowing, and pots of food taken to the field workers. Sashes were also used to spread under the feet of the bride and bridegroom in church and also to support the coffin while lowering it into the hole.

Source: http://www.truelithuania.com/lithuanian-folk-art-top-10-6650

1.Lithuanian cross-crafting is so elaborate and unique that it has been declared UNESCO World Heritage. Wooden crosses and chapel-posts crafted by dievdirbiai ("godmakers") line up Lithuanian roadsides. They may also be found in large numbers in šventvietės ("holysites"). Hill of Crosses with its millions of wooden crosses is by far the most famous one.

2.Amber has been the prime export of local Baltic tribes long before the word "Lithuania" became well known. Balts would sell amber to Roman merchants. Today Lithuania has many amber artisans who make amber jewelry, amber-clad paintings, and other things. Everything with amber is quite expensive; the prices may be smaller in Palanga amber market and larger in boutique stores at city downtowns. If you want merely to learn about amber and its arts, check the Palanga Amber Museum.

3.Verbos of Vilnius are symmetrical colorful compositions of dried flowers and leafs. In Vilnius area churches they are used in place of palm leafs during the Palm Sunday. Vilnius residents usually acquire their verbos at a church-side stall that weekend or at the Kaziukas fair beforehand. Suburban Vilnius has a small Verbos museum open year-round.

4.Užgavėnės hand-made masks represent animals, mythological creatures, ethnicities, and social groups. People wear them during the traditional Užgavėnės festival which aims to "chase the winter away". Generally, by wearing a heavily stylized mask the person aims to "become" somebody else.

5.Sodai ("gardens") are hanging geometric contraptions made of straw. Traditionally used during holidays and weddings sodai now became a symbol of local identity in Lithuania and neighboring countries. Straw is also popularly used to make bags.

6.Margučiai (singular: margutis) are elaborately painted Easter eggs that usually adorn Lithuanian Easter tables. Many games are associated with them, such as "whose margutis is the strongest" or "whose margutis goes the furthest when pushed".

7.Rūpintojėlis is a traditional wooden figure of a sad sitting God (Jesus), who supports his head with one of his arms. The popularity of Rūpintojėlis has been explained by some as being related to the tragic history of Lithuania.

8.Lithuanian textiles (mostly made of linen) are characterized traditional geometric ethnic patterns. They became so symbolic that separate "ethnic strips" are crafted consisting of just an ethnic pattern (many are sold as souvenirs). There is no definitive list of ethnic patterns but Lithuanians can usually feel which pattern is Lithuanian and which is not.

9.Lithuanian traditional household items are typically made of straw, clay or metal (e.g. straw bags, clay cups). While factory-made imported goods have largely displaced hand-crafter items from the mass market, the latter still prevail in city and town fairs. People buy them for their symbolism and a human touch, and they are a popular gift for visitors.

10.Baltic jewelry has made some resurgence recently, with rings, earrings, and other items created based on the finds at archaeological digs.

Folk Art

Source: http://thelithuanians.com/bookthelithuanians/node28.html#section0028

In the simplicity of its forms and its practical application, in the reserved ornamentation and colour scheme, folk art has not departed very much form man's everyday needs. The manner in which applied art objects were executed was greatly determined by the properties of local materials - wood, flax, wool, iron, straw.

Among the surviving arts which have preserved the oldest traditions of Lithuanian folk art are Easter eggs with wax ornaments on them, the verbos or Palm Sunday flowers of the Vilnius region (they are growing in popularity in Poland too), ornamental sashes, bedspreads, tablecloths, towels, pottery, toys, towel racks, decorative distaffs, sabots, gardens" (compositions made of straw), wooden statuettes. In the last few decades paper cuttings and amateur painting have gained a lot in popularity.

Ornament

The roots of the Lithuanian ornament reach down to the formation of the Baltic tribes. There are four kinds of Lithuanian traditional ornaments - geometrical, plant, animal and celestial ornaments. Geometrical ornaments are the most popular. The, ancient plant ornaments conform more to a conventional style than to nature, their connection with nature being often indicated merely by their names. In the animal ornaments the motif of a horse and birds is the most frequent. Celestial bodies - the sun, moon and stars - also have an important place in the Lithuanian ornaments. The ornamentation of tools used every day is usually not very heavy. In the pre-Christian era and early Christian period many ornamental motifs had a symbolic meaning.

The sun motif. All over the world the sun is the symbol of warmth and kindness. It is the most popular ornamental motif in Lithuania. It is very often used on objects connected with various rites, on sashes, Easter eggs, large and small distaffs, glazed ceramic objects, etc. The sun motif was the obligatory element in the iron heads of crosses and chapels, later in wooden crosses as well. The oldest sun motifs are discernible on archeological finds such as amber weights and distaffs excavated on the Baltic shore. The sun, particularly on wooden objects, is represented by a six-pointed star in a circle.

The horse-head motif is second in popularity. It was used on metal objects, excavated now by archeologists. Since the 18th century it has become one of the most popular ways of embellishing gable poles. Sometimes ornamental motifs on sashes remind of horse-heads as well. As a rule horse-heads are rather stylized.

A PLANT IN A FLOWER POT is an ornamental motif which is third in popularity and is very often used on ancient dowry chests, beds, towel racks, window shutters, pots, distaffs and, more rarely, on home-made fabrics. This motif appeared in the 16th and 17th centuries and gained its greatest popularity in the 18th century. Most often it is a lily or a tulip in a pot, vase or wine glass. Sometimes above the plant or among its branches there is one, two, three, five, seven or even more birds. The blossom may be replaced by the sun symbol and this is very often done on distaffs.

Crosses

At the turn of 20th century German, French and Polish scholars recognized wooden crosses and chapels as one of the most typical features of Lithuanian culture. To this day many publications on Lithuanian folk art attach great importance to these objects. Most of the Lithuanian crosses and chapels are very artistic. They used to be erected at farmsteads, streams, roads, at the end of a field and other places. They used to be erected on various occasions - the birth of a child, a sudden death, the beginning of the construction of a farmstead and other such events.

At the beginning of the 20th century crosses and chapels in Zemaitija were spaced by several score of meters. Lithuanian crosses and chapels were more ornamented than in other countries. For a long time they were indicators of the farmers' wealth and social position. Young girls used to be judged by their flower gardens and the crosses in their farmsteads.

Most crosses were built with a single cross bar, but there were also crosses with two cross bars, especially in Zemaitija. The latter type of crosses were usually erected in times of plague or other great disasters. Ornamentation depended on the form of the cross. Crosses in western Zemaitija were the least ornamented.

Sculpture

Every Lithuanian chapel used to contain statuettes of more than 40 saints, the number of which in each chapel amounted sometimes to more than a score.

In the 1930's Koncius covered 2424 kilometers, traveling in Zemaitija, and he registered 3234 statuettes of saints, which means there was one statuette for every 700 meters. The most frequent was the sculpture of the Crucified (42,8 per cent) and of the Holy Virgin (22,7 per cent), others included: St. John (9,3 per cent), Jesus (4,4 per cent), St.George (2,8 per cent), the Pensive Christ (2,5 per cent), St. John the Baptist and Roch (2,3 per cent), St. Barbara (0,8 per cent), St. Joseph (1,1 per cent), St. Anthony (1,78 per cent), St. Isidore (0,8 per cent), St. Florian (0,7 per cent) and others.

Very typical of the surviving Lithuanian sculptural tradition are the images of the following three saints - the Pensive Christ, St Isidore and St George.

The Pensive Christ is depicted as an old man sitting with his chin on his right palm. But he is not Christ in prison. In small chapels with open sides, attached to trees, the Pensive Christ is usually the only statuette. He symbolizes sadness, as his crucifixion was a sacrifice to humanity to alleviate its pain and wipe its tears. During and after a war Lithuanians looked upon the Pensive Christ as a symbol of their misfortunes.

St George (Gr. Georgios - "land tiller") is very popular in Lithuania. Together with St Casimir he is considered to be Lithuania's second saintly guardian. He is usually depicted as a rider, slaying a dragon to defend a princess. To the peasant St George is the guardian of his animals. A chapel with his statuette was usually placed at the gate through which animals were driven to and back from pasture.

St Isidore is depicted as a farmer sowing grain while an angel is ploughing the field. When St Isidore is depicted ploughing the field, the angel is sowing. St Isidore looks after the fields, protects them against drought or too much rain, stimulates the sprouting of seeds. Therefore his statuette is usually placed in a chapel on a pole in the fields.

Wrought Iron Artifacts

Wrought iron artifacts such as chests, carts, door fittings and window gratings make a separate branch of folk art. But wrought iron crosses and wrought iron heads of chapels are most expressive of the folk artists' talent and of the spiritual world of the Lithuanian nation. The cross usually passes into sun rays which sometimes include blossoms and leaves of tulips, rues and other flowers, and sometimes a moon and stars.

Fabrics

Halt a century ago all Lithuanian women used home-made fabrics. In Dzukija this continued right up to the 60's. Even now home-made towels, tablecloths and bedspreads are admired as pieces of folk art. Mostly they are made of linen. Their beauty is based on the combination of patterns and colours. The majority of patterns on white linen cloth are based on ancient geometrical ornaments which symbolize the sun and other natural objects. The central pattern is usually composed of several uncomplicated but contrasting elements framed by smaller compositions. Their main peculiarity lies in their constancy and rhythmic repetitions. The same patterns but of different proportions are used on separate articles of the same set. The weaving pattern is usually in harmony with the proportions of the object, e.g. a table, for which the article is used. With time, the compositions became freer.

The weaving patterns of bedspreads are based on geometrical ornaments, composed of squares, catpaws, suns and the like. In south-eastern Lithuania catpaw patterns are smaller. The same patterns are used on fabrics woven with a different number of warps. But naturally, with the increase in the number of warps the patterns become more complicated. With time plant and animal motifs appeared and now they are often combined with geometrical patterns. Colour introduces a still greater variety. Cloth woven with two warps is usually striped.

A lot of attention was paid to colours. Striped or checked bedspreads do not have many colours, usually two, three or four. Dominating colour combinations are black, green and red; green, white and red; black and red.

Palm Sunday Flowers

It is supposed that the first Palm Sunday flowers appeared in the Middle Ages to enliven festive processions. In the second quarter of the 19th century they were already wide-spread, but they were mostly used for decorative purposes and never had the same ritual function as the Palm Sunday bunches of willow, yew and other green twigs had.

Palm Sunday flowers are made of field, forest, water and garden plants. At the present time 45 kinds of plants are known to be used for this purpose. 11 kinds of plants (mostly reeds) go for the heads alone. Preparations for the production of Palm Sunday flowers begin in July. Women and children start collecting cudweeds, rye and oat ears, timothy grass, immortelles and other plants in summer. The brightness of the colours depends not only on the kind of the plant bus also on the time when it was picked. The plants are spread or hung in bunches in attics to dry and wait till they are used to make Palm Sunday flowers. Mosses, lichens, various lycopodiums are collected just before making Palm Sunday flowers.

Palm Sunday flowers have several shapes, that of a rolling pin, a wreath or a rod. They may be flat or irregularly shaped. All Palm Sunday flowers are started in the same way. A bunch of reeds and bents is tied to the top of a 30-to-50 centimeter long nut-tree rod and then dried plants and flowers (sprinkled with water so that they should not crumble) are arranged down the rod and fixed to it tightly with a thread.

Easter Eggs

Decoration of Easter eggs is a very ancient custom. At the foot of the Gediminas hill in Vilnius archaeologists have found eggs made of bone and clay, which shows that this custom was known in Lithuania as early as the 13th century. Easter eggs are mentioned by Martynas Mazvydas in his dedication to his book "Hymns of St. Ambrosius" (1549). Easter eggs were particularly popular at the turn of the 20th century. They were decorated both by the grown-ups and the children, by the rich and the poor. Some were dyed in a single colour, some were decorated in patterns. Decorations were produced by painting pat- terns on a warm egg with the tip of a stick or a pinhead dipped in hot wax. Droplet-shaped strokes were grouped in patterns, twigs of rue, little suns, starlets, and snakes. The most frequent pattern was that of a sun, like those on large and small distaffs. Smaller patterns were joined by dots and wavy lines into larger ornaments. Their combinations were so varied that it was impossible to find two identical Easter eggs. Every village had its own best egg-decorators.

The painting of decorations in wax completed, the egg was dipped in black, brown, red or green dye. Up until the beginning of the 20th century natural dyeing materials were used such as onion peel, birch leaves, hay, oak or alder bark. Very popular was the black dye produced by soaking and boiling a mixture of alder bark and rust. Dyed eggs were placed in a hot oven or hot water for the wax to melt. Patterns in several colours were produced by painting them with wax on a lighter colour and placing the egg in a darker dye. Similar patterns could also be scraped with the tip of a knife.

Many nations believed that eggs, particularly decorated eggs, had a magic power. When the animals were first driven to pastures in spring, the farmer's wife used to place an egg on the threshold to keep them in good shape. The farmer used to place an egg in the first furrow ploughed in spring to ensure a good harvest.

Straw Compositions

Straw compositions were used to decorate rooms on various occasions, Christmas trees and the place at the table where the bride and bridegroom sat. Straw compositions are a separate branch of folk art which was very popular in the first decades of the present century. The basic element of every straw composition is a segment made of 12 pieces of straw strung together. Rye straw is sprinkled with water and cut into 12 equal pieces. 8 pieces are strung on a thread the ends of which are tied. Then the string is bent into a figure of eight, folded and the tips tied. Each of the four remaining pieces of straw is strung on a thread, one end of which is tied to each corner of the segment. The other end of the thread is used to join the segment to another one. There is also another method of making straw compositions: three segments of a different size are tied one with another and suspended on a common thread to rotate in the wind. To mark the Epiphany, stars made of pieces of straw of different length were used to decorate rooms.

The most complicated and beautiful straw compositions were "wedding gardens" which were popular in Aukstaitija. These compositions were large, made of a large number of segments. Suspended from its corners are birds, stars and the "gardener". Lithuanian emigrants to the United States use straw compositions as Christmas tree decorations. There are more than 60 kinds of such decorations.